INTRODUCTION :

Hussey is a British artist born in London in 1990 where he still resides. His artworks are emotionally raw, created primarily through the paradoxically laboured and intricate mediums. His textiles utilise a collage technique of embroidery, appliqué, digital printing, and silkscreening...

Read more/less

He often uses vintage fabrics that imbue his artworks with a physical and symbolic weight, weaving history into his works. Hussey draws inspiration, particularly in his word based pieces, from historical union banners akin to those used during the British miners’ strikes, for their palpable conviction and guttural impact. Whether through an expanding vocabulary of quasi-mythological symbols, or embroidered lines of text extracted from weighted performative situations, he explores both personal, national and universal identity, often in response to aggravating relationships and events. The dramatic and intense impression created by these works is heightened by a vibrant and bold palette, which is used to both reinforce its narrative as well as underline the labour-intensive aspect of his practice. The resultant larger-than-life scale artworks have a commanding presence, both reverential and awe-inspiring. Further developments have ensued with other materials including glass, bronze and monoprint revealing a deeper concern with control and chaos and the sweet spot in between these two distinctive states.

Hussey studied Textiles at Chelsea College of Art before completing an MA in Textiles at the Royal College of Art. His work is widely respected and has been exhibited in notable exhibitions including The Textiel Biennale 2017 at Museum Rijswijk in the Hague, a solo presentation at Art Central in Hong Kong, the Bloomberg New Contemporaries in 2014 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, the Royal Academy London and Volta New York and the Young Talent Contemporary Prize at the Ingram Collection in 2016. Hussey has participated in residencies at La Vallonea, Tuscany, Italy in 2018 and will participate in a residency at Palazzo Monti, Milan in 2020. His work is held in collections worldwide including Simmons & Simmons, Hogan Lovells, The Groucho Club and Soho House.

EXHIBITION ARTWORK IMAGES :

EXHIBITION INSTALL IMAGES :

ONLINE CATALOGUE (click below) :

EXHIBITION INTRODUCTION :

Hussey states “I have killed Henry over and over again, because the only way to grow as a person is being willing to sacrifice what you hold dear and identify with, to eliminate the qualities which over time get in the way, stripping the ego in order to progress”...

Read more/less

At a time of crisis, a palpable murmur arises, suggesting to many of us that if we rip down the established order perhaps we could re-form a pure new world of optimistic possibility. Ah, but what happens when we meet the first person who doesn’t agree with our new world vision? Well, to create any substantial societal change, first we probably need to accept and allow for a dose of anarchy, and perhaps a little dash of bloodshed. If there are those that stand in the way of the potential of our utopia, maybe it’s off to the work camps, or perhaps we just eliminate them and make the issue go away… If you look throughout human history any significant change, usually results in atrocity. Friedrich Nietzsche approached the problem of nihilism as deeply personal, stating that the predicament of the modern world is a problem that has “become conscious” in him. According to Nietzsche, it is only when nihilism is overcome that a culture can have a true foundation upon which to thrive. ‘We Live in the Remains of the Gods’ alludes to the pre-existence of our collective foundation. Hussey cites huge rises in cases of depression resulting from personal isolation as a sickness within our society and vulnerability of our species. “We need something to believe in” he states. “Whether it’s the weather God, family, meaning, purpose, sun deity, a man on a cross… having belief is an inherent part of our humanity. All humans have a black hole inside ourselves, which must be filled to nullify the pain. We have tried, and largely failed to fill it with consumerism and capitalism… We all need purpose and meaning to sustain our existence, as that’s the only thing that makes the suffering worthwhile.”

In 2016, Hussey began making reactionary work, he states that he had “stopped believing in what he was saying”. Having read a book about the atrocities of the 20th century titled ‘Maps of Meaning - The Architecture of Belief’ by Jordan B Peterson, the conclusion that the he came to, was rather than trying to use a collective ideology to change the world, instead you change yourself. So you must attempt to remove all the suffering from your own existence and build your own life on solid ground before attempting wider change. The immediate result is to help the closest people around you, who may in turn be compelled to try to change and alleviate their own suffering and then in turn help others, creating a chain reaction. This form of individualism has the potential to lead to the benefit of all. Prior to this point Hussey’s work could be seen to represent an egoistic belief that his personal narrative represented the universal. Yet the work in this exhibition indicates a rotation of thought, where the universal is represented through the personal experience, and becomes an acknowledgement of one’s own humility.

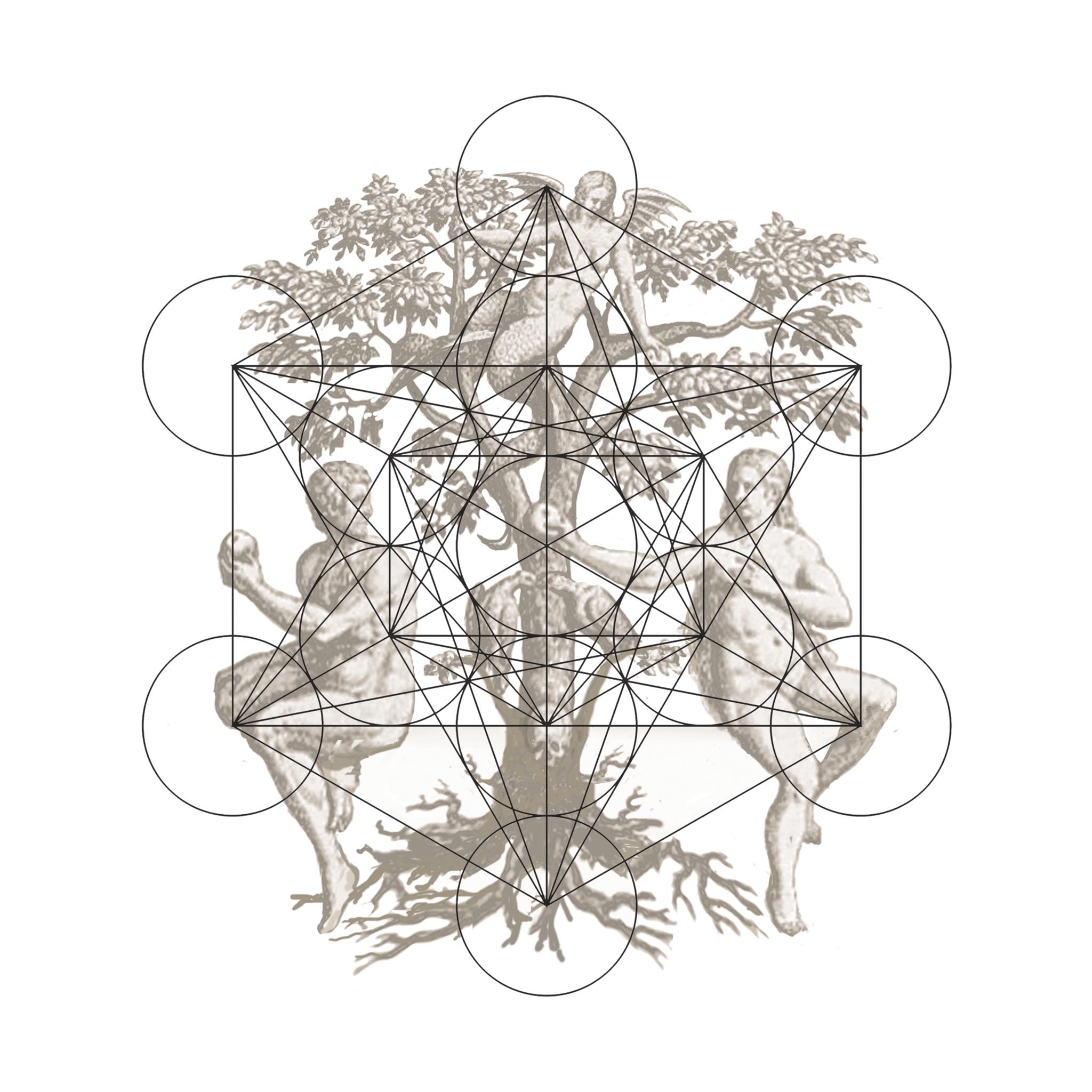

‘We Live in the Remains of the Gods’ is loaded with archetypical and symbolic, cross cultural, imagery and ritual, which Hussey uses as a way to examine truth and reveal our shared foundations. This search runs deep, as Hussey suggests that it is something we are now lacking as a society; “when a culture lacks truth and lies collectively, what typically happens to it throughout history, is that there is a fall or flood or destruction. I’m using this imagery as a warning, that when you embrace falsehood, you’re not just betraying yourself, you are also putting society at risk.”

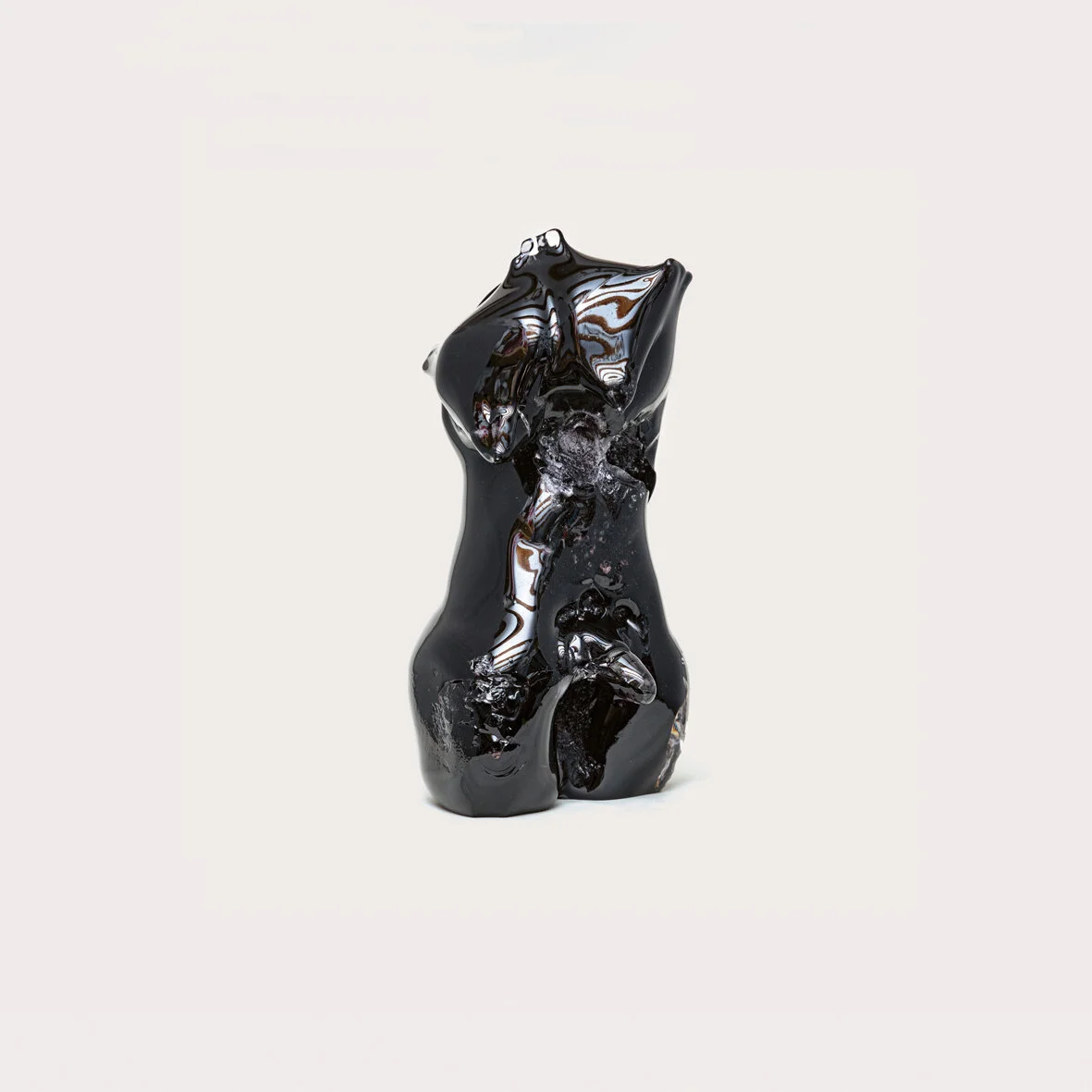

For Henry, his form of individualism takes the form of sacrifice, which is a central theme to the work, that you must be willing to give everything, even the most intimate parts of yourself, in order to obtain your vision. It is a vision explored in multi-media, where each material choice is selected for its conceptual weight and potential. Part of the reason he enjoys working with craft mediums, which are technically proficient methods, is that they require skilled expertise, which can then be undermined or corrupted with unexpected action or imagery. Hussey’s works are first exquisitally constructed and then become subjected to irrevocable actions upon them. Textile is a utilitarian medium that has been used throughout history to proclaim and present the significant moments in a civilisation. It carries with it a way to emblazon important messages and unite towards a common cause. Glass is an extraordinarily physical medium that you cannot walk away from once the process begins. Once cooled, it becomes solid and hard yet when pushed it breaks, an analogy which fits the human condition perfectly. The glass works (representing Saints and Martyrs) have been put through extreme acts of violence in their genesis, yet uphold a moral virtue.

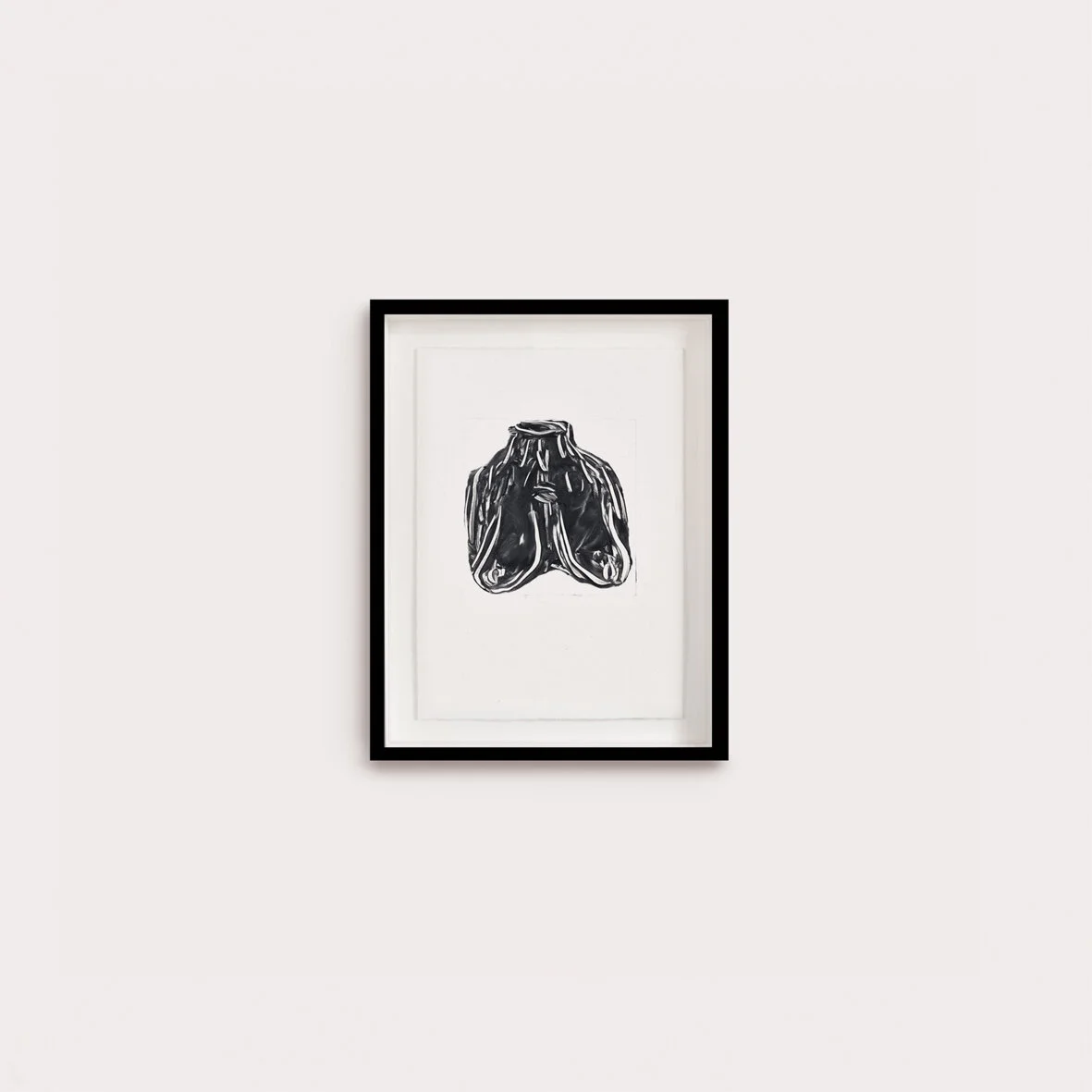

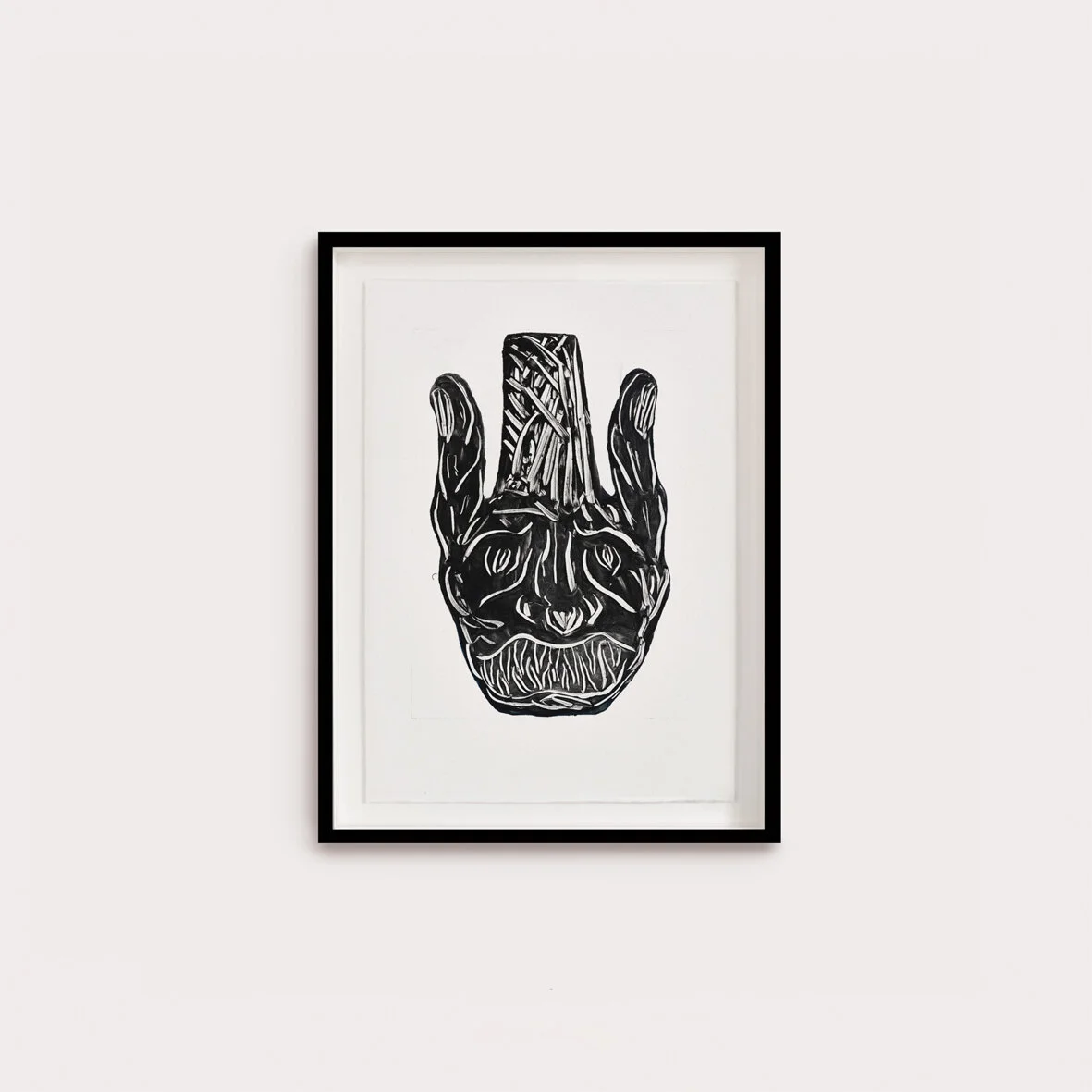

The monoprints developed, and were inspired by, the immediacy of the glass making process. They primarily reference sculpture from Greek and Roman antiquity, yet are also seen as various aspects of self portrait. The finality of the process, as once it has gone through the press it is done, is appealing in its honesty, openness and vulnerability. The film works are expanded from dreams which have been fused with elements from mythological and religious stories. Hussey is naked, front and centre in these works, yet he is playing a character and inhabiting a role, where universal ideas are represented through the most personal of spectrums. Expanding from his use of performance in his work, they are captured, yet ephemeral, which allows him a wider exploration than the physical mediums can allow in isolation. For Hussey a commonality between mediums is a learning of, and expansion beyond, the accepted boundaries of that medium, to take it in its pure form and brutalise it revealing its capabilities, strength and vulnerability. Beauty and barbarism seem like accurate representations of human duality, and allude to a blossoming deriving from pain.

I ask Henry what he hopes people will think of this challenging exhibition, he answers “I am willing to alienate everyone because I know it is right and the decisions I am making are the correct ones. I think the past few years have made me far more formidable as an artist. I think the show is about history and culture and the cyclical nature of it and you need to have respect for the past, even when you’re in the midst of heated exchanges, you need to take a step back and look at the wider picture, not just of the current situation but how the situation has been played out throughout human history… I just read that back, and it sounds like I am talking about Brexit doesn’t it?!” He isn’t… A long line, when followed, leads us from the present to the origins of our collective and personal mythology.

Joseph Clarke, 2019

PODCAST | HENRY HUSSEY IN CONVERSATION WITH JON SHARPLES :

HENRY HUSSEY / WE LIVE IN THE REMAINS OF THE GODS by Jon Sharples :

This is the pivotal line in ‘Change’, the two-channel semi-autobiographical short film included in Henry Hussey’s new solo exhibition ‘We Live in the Remains of the Gods’.

Hussey is a man animated and sustained by an almost megalomaniacal conviction of the universal nature of his own personal struggle. Is humanity doomed to repeat its mistakes? He invites us to take that possibility seriously by looking at the world through the lens of ‘archetypes’ – the Jungian hypothesis that all humans share a collective unconscious whose building blocks can only be inferred indirectly from our stories, art, myths, religions, and dreams...

Read more/less

Some tropes appear again and again in civilisations across time and place: the nourishing mother, the hero, the trickster, the strong man, the apocalypse, the deluge, the creation, the ultimate sacrifice, God. It’s fair to say that Jung’s ideas have been somewhat superseded in the day-to-day practice of contemporary psychotherapy, but nevertheless one possible explanation for the near ubiquity of certain motifs and complexes is that people have an innate predisposition to respond to, organise and interpret the world in a certain way - the psychic counterpart of instinct, analogous to Chomsky’s theory of the language acquisition device and a Universal Grammar that is genetic rather than learned.

It is never totally clear whether, ultimately, Hussey is an optimist or a pessimist. On the one hand, his wading through the detritus of half-remembered myths, inherited legends and fragments of faded grandeur seems to be a suggestion that the Enlightenment is, at best, a work in progress. On the other hand, there is the glimmer of hope that culture itself is the way out of the cycle of hubris and nemesis. Having complexes is not pathological, as everyone has them. What is pathological, however, is thinking that we don’t. Jung clarifies, “Everyone knows nowadays that people ‘have complexes’. What is not so well known, though far more important theoretically, is that complexes can have us.” Perhaps Hussey’s message is that we don’t need to get rid of our complexes: we just need to become consciously aware of them.

Knowing oneself is always likely to require some prolonged self examination and an element of delayed gratification. If there is a convoluted and time-consuming process for image-making then Hussey has probably given it a go. He burst onto the art scene a few years ago with his confrontational textiles, which, through their intricate and labour-intensive nature, have tended to hint at the determined, intense, slow-burning rage required to see them through. To those works he has added a sophisticated yet raw, series of glass sculptures and monoprint drawings, both of which involve a revelling in the tension between fits of passion, spontaneity and even violence, and patient craft skills. The works on paper and in glass share a satisfyingly complementary sense of translucent solidity arrived at by accretion of marks and material. In the same way that Hussey’s macho sewing deliberately plays against the expectations of gender constructs, so too do these gorgeous glass forms, tempting the viewer into categorising them with Jean Paul Gaultier’s fragrance bottle paradigms of ‘homme’ and ‘femme’, while embodying a fluidity that speaks to a more complex reality.

There is significant unwelcome pressure on artists working today to rise to this historical moment and make expressly ‘political’ or, even worse, ‘useful’ art. A couple of years ago, Henry made the deliberate decision to turn away from the autobiographical and self-indulgent in favour of a more literal commentary on current affairs – something he now feels has not dated well. ‘Idolatry’ is a work which purges one such ‘mistake’ by condemning the old work to the verso, flipped and replaced with a form of self portrait and with it an insight borrowed from second-wave feminists that the personal is political because the person is political. ‘The Best And Worst Parts Of Ourselves’ diptych makes even more ambiguous use of the limp polyester Union flags that punctuate the high street in Hussey’s home town of Weybridge with plastic patriotism. The Masonic Eye of Providence atop both of the figures creates a cyclops common to tales from Odin to the Odyssey and a host of places a long way from leafy Surrey.

By wrestling with the archetypal patterns through the symbols they manifest in the psyche, Hussey is grasping at an expansion of consciousness. Such an expansion, Jung believed, was of paramount importance, for as he put it, “Man’s task is…to become conscious of the contents that press upward from the unconscious. […] As far as we can discern, the sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a light in the darkness of mere being.” And that’s also the thing about mistakes – if you throw them on the fire they’ll generate light for you.

Jon Sharples, 2019

Jon Sharples is an art lawyer, broadcaster and independent curator. He is on the boards of Block 336 and the Liverpool Biennial